This new collection contains my piece on “Facts, Possibilities, and the World: Three Lessons from the Tractatus”

Category: Uncategorized

A BRAVE STAND FOR FREE SPEECH

Chung Pui-Kuen, the former editor of the now defunct Hong Kong STAND NEWS, is currently on trial for publishing a number of “seditious” articles. Stand News trial: Ex-Hong Kong editor accused of sedition says politicians should be free to criticise authorities – Hong Kong Free Press HKFP (hongkongfp.com)

In defense of his editorial decisions Chung has told the court that “the space for free speech should permit the most fierce criticism and accusations, especially when the target is the authorities,” because government corruption might otherwise be the result. And he warned that “the government’s suppression of critical voices or opinions will cause hatred more easily” than any articles published in Stand News. Chung defended, in particular, the publication of two interviews with two politicians from the democratic opposition.

It was important that their voices were heard and preserved for the historical record, he argued, “Some would say journalism is to provide the first draft of history. While it can be flawed, incomplete, or with potential mistakes… at least it provides a basis for future discussions.”

Chung’s words are particularly remarkable because they were spoken at the same time as Hong Kong’s big show trial against 47 of its former democratic leaders is under way. His words sounded like a ringing defense of their right to speak and to hold the opinions they did. Their trial is certainly extraordinary. The 47 are accused of behavior that in other places would be considered part of the normal business of politics: organizing to win an election, trying to select the most promising candidates, proposing to stop the government’s budget, if they won a majority, and possibly even forcing the government to resign. But the authority’s understanding seems to have been that they were allowed to run only as long as they would not win and would be unable to enact their proposed policies.

LIMITS OF INTELLIGIBILITY

With my own contribution “Wittgenstein on the Limits of Language” – part of my grappling with the Tractatus.

For China’s intellectuals, restrictions started long before the pandemic and will continue after Covid is over

SOUTH CHINA MORNING NEWS

Guo Rui Jun Mai in Beijingand William Zheng in Hong Kong

Published: 10:30pm, 2 Jan, 2023

For Sheng Hong, a prominent economist based in Beijing, in-person academic events and overseas trips were restricted long before the Covid-19 pandemic, and they are likely to outlive the pandemic too.

As Sheng tried to host a biweekly panel discussion in the summer of 2018, the small group of scholars were expelled and forced to move twice during the half-day meeting.

They ultimately wrapped up their discussion of complexity economics, a cutting-edge branch of economics, on the pavement.

Later that year, on his way to a conference at Harvard University, Sheng was stopped at an airport in Beijing by the authorities who warned that his travel posed a threat to state security.

He was director of the Unirule Institute of Economics think tank which promoted liberalisation of the country’s economy and that was shut down by the government in 2020.

“It started before the pandemic,” said Sheng, referring to Beijing’s rules in the name of preventing Covid-19 that restricted in-person events and international travel.

“The direct reason is simply restrictions set by the authorities.”

Sheng is among a number of Chinese intellectuals who have found it increasingly difficult to publicly express their academic views or exchange them with fellow scholars, especially when those views are at odds with those held and promoted by the Communist Party under the leadership of President Xi Jinping.

Since Xi assumed power in 2012, he has conducted a far-reaching project to reshape the country’s intellectual and ideological outlook. During the 20th party congress in October he declared that in the past 10 years China’s ideology landscape had seen an “all round and fundamental” improvement.

The project, as Xi summarised in a series of speeches over the decade, involves chipping away all platforms or spaces where views are unflattering to Beijing, as well as flooding the public discourse with narratives and values favoured by the party.

According to scholars who spoke to the South China Morning Post, at universities the evaluation of professors in the social sciences has become more focused on their contribution to the party’s ideology, and people who dare to deviate from it must constantly look over their shoulder for student informants and surprise inspectors sent from high authorities.

The scholars expressed concern that these settings would seriously impair the ability of the country’s intellectuals to expand their knowledge in social sciences, as well as the next generation’s ability to think critically, a trend some said had already become obvious.

A literature teacher at a Guangzhou-based university surnamed Liu – who did not wish to give her full name due to the sensitivity of the subject – said at each faculty meeting she was reminded she was not supposed to talk to students about seven subjects. They include universal values, press freedom and civil rights.

Those seven topics were designated taboo in college courses in 2013, the year Xi became president, and have since been established as a firm red line in ideology in Chinese universities.

“The [school’s] secretary emphasised that at almost every meeting,” Liu said. “So in classes, we need to conduct some self-censorship and think of a way to say certain things so it’s acceptable to all, including the student informants.”

In her classes, Liu must navigate talking about women writers without getting too much into feminism, and determine how to teach the Divine Comedy with as few details about Christianity as possible.

Any scholar without a clear state affiliation seeking to publish findings on Hong Kong, Taiwan and Muslim groups in China could expect to be rebuked by Chinese journals, she said. She added that invitations to any guest speaker in class must be preapproved.

A direct result of these restrictions on social sciences is that the country has stopped acquiring new knowledge on those topics, according to a Beijing-based political scientist who spoke on condition of anonymity.

“All these censored areas have stopped developing,” the person said. “Look no further than the Cultural Revolution. The studies abroad are much better than those inside the country. There is almost no one studying it now.”

In addition to the various restrictions on topics available to be studied, Chinese scholars are assessed under a system based on political indoctrination, with various Marxist schools and university courses at its centre, according to a professor surnamed Li who teaches media studies at a university in Guangdong.

“Regardless what subject is being taught, one needs to establish some links between it and Xi’s thoughts,” said Li, referring to the president’s political theory that has been enshrined in the state constitution since 2018.

“Once you spend all your daily energy on these things, you become a different person. You’ll be unable to conduct international academic discussions, address trending social topics, or anything a real scholar is supposed to do,” Li said.

By March, there were more than 1,400 Marxist schools inside China’s universities, according to the Ministry of Education. There has been a rapid proliferation in recent years of these institutes, which were set up not only in comprehensive universities but also medical schools and art academies around the country.

They are heavily focused on courses as well as studying the achievements of the party’s governance, especially under Xi.

In various speeches in the past 10 years, Xi has repeatedly called for the work on thought politics – or political indoctrination – to permeate “the entire process” of education in colleges and universities.

He has also said the ultimate purpose of education should be to train for the future of China’s political system.

“We need to be clear about the goal of educating people, and it’s very clear that the goal is to nurture builders and successors of socialism,” he said in a 2019 speech. “If we spend much time nurturing people who are grave diggers of our system, what is the point of education?”

But in the fresh faces joining her university, communications professor Li noticed an obvious pattern of students’ weakening ability to analyse.

“The consequence is they are getting worse at critical thinking,” she said. “The homework I’ve received after the pandemic is very different from that received before it. And there’s blatant hostility towards foreign matters.”

The intellectual landscape in China’s social sciences has even troubled some of the firmest supporters of the Communist Party and staunchest defenders of its policies.

“The US and the West kicked off decoupling with China in high technology and that made people here realise technology is the fundamental power of innovation. And my understanding is that ‘original ideas’ in social science matter just as much,” said Zheng Yongnian, director of the Institute for International Affairs at Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen.

Zheng said a thinker was “not something that could be brought up, but something that grows in a tolerant environment”.

Official interference with academic work must be minimised so scholars could have room to research and express themselves freely, he said.

Zheng is a seasoned political scientist well respected by the Communist Party. He was among a handful of scholars invited for a 2020 lecture for the Politburo – the country’s highest policymaking body, led by Xi – on China’s five-year plan.

But Zheng said that given China’s academic environment – made worse by a rigid evaluation system heavily focused on the publishing of papers – it would be a “fairy tale” to see important thinkers on social sciences emerge.

“The evaluation system [for scholars] here is simply suffocating people’s minds,” he said. “China is now big on the number of papers being published, but small on original ideas.”

Sheng Hong used to sit on a panel of 50 economists that advised the Chinese government. The panel was co-founded in 1998 by Liu He, the outgoing vice-premier.

Sheng is among a handful of prominent economists who lost their seat on the body during a reshuffle in 2019. During that reorganisation, a few officials in regulatory agencies gained seats.

The Beijing-based economist does not know how his activities are still being restricted in 2023.

“The only way to figure out if I’m still on the exit ban list is to try to fly out,” he said. “It’s so tiring after preparing all the materials for academic conferences and being stopped at the airport.

“Academic development is doomed to be stalled, and so is cultural diversity and the general public’s knowledge. The public is no longer in somewhat neutral information surroundings.”

Is there a common good?

Both conservative and leftwingers have maintained that there is a common good which we should set out to realize. But other conservatives and leftwingers have declared with equal conviction that there is any such common good. Could it be that both sides are unclear about what is at stake?

The case against the assumption of a common good is usually made in the name of moral pluralism or individualism. The claim is that there exists a plurality of different conceptions of the good which can lay equal claim to validity. In one version of this claim, this moral pluralism manifests itself in the existence of different cultures; another, more radical version assumes that moral pluralism is grounded in human individuality.

Stuart Hampshire argues vividly argument against the idea of a common good t in his 1989 book Innocence and Experience. He asserts that the only thing that can hold society together is a commitment to procedures for negotiating our moral differences. The key to the social order is what he calls “procedural justice” — which he contrasts to a substantive conception of justice which, according to him, is always the expression of a particular understanding of the good. Procedural justice, he writes, is a means for enabling human beings “to co-exist in civil society, to survive without any substantial reconciliation between them, and without a search for a common ground. [My emphasis] It is neither possible nor desirable that the mutually hostile conceptions of the good should be melted down to form a single and agreed conception of the human good. A machinery of arbitration is needed and this machinery has to be established by negotiation. Justice can then clear the path to recognition of untidy and temporary compromises between incompatible visions of a better way life.” (p. 109)

This account suffers from a number of flaws. The first is that it treats conceptions of the good as if they were necessarily disjoint. But we know from history and experiences that such conceptions may overlap in part and that the communalities they share may serve as a basis for mutual recognition and peaceful coexistence in society. We also know that parties that meet will try not only to identify existing common ground but set out to create new such ground. Societies are never held together only by a shared sense of procedural justice. they also seek to foster common sentiments.

We must accept that there is no complete vision of a common good shared by humanity at large and that there cannot be such a thing. But that should not deter us from striving to achieve a limited sort of social consensus. This is, indeed, what we generally set out to do in politics. We can, for that reason, characterize politics as an ongoing search for a common good. But we must allow at the same time that there is no single ultimate good of this kind to be found. Our search does not have a single, fixed target. We must also acknowledge that even when we agree, for the time being, on a particular conception of the good, there are likely to be those excluded by that conception. Social consensus is never the consensus of everyone in society.

Philip Pettit talks to Johnny Lyons

INNOCENCE AND EXPERIENCE: Stuart Hampshire on morality and politics

Stuart Hampshire’s book Innocence and Experience from 1989 is one of my favorite works in philosophy. Hampshire’s star in philosophy seems to have faded somewhat, but his work deserves our continued attention. Innocence and Experience is an original and provocative work of philosophy. It is also a testament to its author’s humanity, experience, and wisdom.

The book brings together and elaborates ideas about morality that Hampshire had first voiced in earlier years. It has illuminating things to say about the importance of conditional judgments in morality and elsewhere, about the difference between substantive and procedural justice, and the role of imagination in moral thinking. Hampshire’s critique of Aristotle’s psychology with its overemphasis on reason is well-taken. So is his criticism of Hune’s detached treatment of morality. And so is also his critique of John Rawls’ attempt to pin down substantive principles of justice.

Hampshire is particularly clear-sighted on the difference between morality and politics. “Observation of the politics of the immediate pre-war years, ” he writes, “first made me think about the unavoidable split in morality between the acclaimed virtues of innocence and the undeniable virtues of experience.” And he complains that “most Anglo-American academic books and articles have a fairy-tale quality because the realities of politics, both contemporary and past politics, are absent from them.” With his background as a diplomat as well as a philosopher, Hampshire is keenly aware of the difficulty of maneuvering the gap between moral principles and the practical necessities of human politics. There is, he thinks, no theoretical resolution of that issue. “Once again the philosophical point to be recorded is that there is no completeness and no perfection to be found in morality.”

Hampshire’s view of our moral virtues and capacities is expansive: “Courage, a capacity for love and friendship, a disposition to be fair and just, good judgment in practical and political affairs, a creative imagination, generosity, sensibility: tese are all dispositions and capacities which are grounds for praising men and women.” But we know, he adds that historical circumstances and personal preferences and choices limit our ability to pursue all those virtues at once. Some of them are, indeed, incompatible. “Lopsidedness is a fact of human history and therefore a fact of human nature.”

What I appreciate most in the book is that Hampshire is writing from a broad range of human experience. His book gives testimony to a mature and humane wisdom as well as to exceptional philosophical acumen.

I remember Stuart Hampshire with gratitude as a friend and mentor and teacher of philosophy.

Xi Jinping: From collective to authoritarian government

About a year ago, at the end of 2021, The State Council in Beijing published a remarkable document with the title: “CHINA: A DEMOCRACY THAT WORKS,” It argued that China had developed a “whole process democracy” that was, in fact, superior to its Western model which consisted of an array of democratic practices at various levels of government and society.

The description of these practices was, indeed, intriguing, though one was left with the question to what extent they were implemented in a way that preserved their democratic character. At every point, the document insisted that they would of course have be “under the guidance of the Communist Party.”

But the document certainly revealed the democratic aspirations in some China’s leadership. We should certainly not take their expression for mere propaganda. The question is only whether those sentiments are shared at the highest levels of the Chinese government and specifically by its supreme leader, Xi Jinping.

What gives reasons for doubt is Chi’s apparent preference for authoritarian rather than collective government. The “Democracy” document had given an explicit endorsement of collective government. It said:

“China draws on collective wisdom and promotes full expression and in-depth exchange of different ideas and viewpoints through democratic consultation. Parties to these consultations respect each other, consult on an equal footing, follow the rules, hold orderly discussions, stay inclusive and tolerant, and negotiate in good faith. In this way, a positive environment for consultation has been cultivated in which everyone can express their own views freely, rationally and in accordance with the law and rules. Through democratic consultation, China has built consensus and promoted social harmony and stability.”

This appears to be far from Xi’s preferred way of governing as his recent re-organization of China’s government makes explicit. It was Deng Xiaoping who had implemented the system of collective leadership in order to prevent the excesses of the Mao period. In a 1980 speech Deng had criticized the “overconcentration of power” and had emphasized the need to guard against a future political strongman. Chi as now gone back on those reforms. He has, instead, taken full control of the political system arguing that a concentration of power was necessary as a solution to the acute political and economic problems faced by China.

It seems that China is right now moving further away from democracy> I wonder what the authors of CHINA: A DEMOCRACY THAT WORKS are thinking.

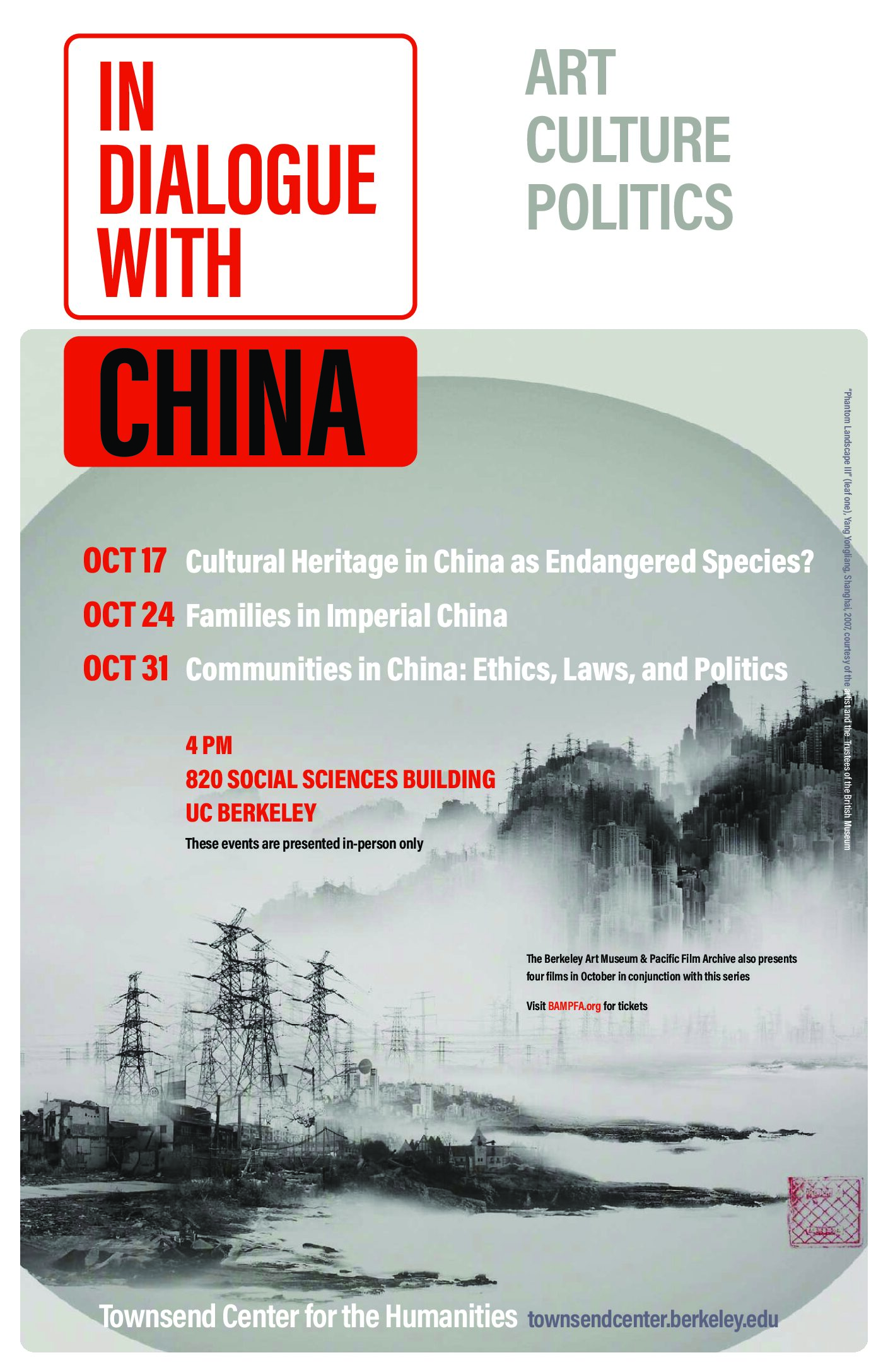

In Dialogue with China

IN DIALOGUE WITH CHINA: ART, CULTURE, POLITICS

“This yearlong series, held in Spring and Fall 2022, brings together Chinese and Western panelists to engage in cutting-edge dialogue on China’s complex contemporary reality.” Townsend Center for the Humanities

https://townsendcenter.berkeley.edu/events/in-dialogue-with-China